andreas malm has in the last few years written 3 very good books on this sort of thinking about climate crisis, accounting for the wider political totality (that is, the political economics and power dynamics of climate change). much higher-level analysis than 'personal carbon footprints' and 'but india'.

Malm’s recent work builds on the arguments of Fossil Capital (2016), in which he showed that Britain’s embrace of coal came relatively late – water power remained dominant for decades after Watt’s invention of the steam engine. Fossil capitalism arose from a desire to concentrate industry in cities, thereby avoiding the complex engineering needed to sustain water-powered production, which would have necessitated co-operation between mill owners; it also allowed for a greater concentration of labour, more easily disciplined and exploited. It’s possible to imagine an alternative industrialisation, based on wind and water (but today including solar power), but it would have required far greater diffusion of production and thus resulted in greater bargaining power for industrial workers. Instead, a particular social configuration, stained with smoke and soot, became the pattern of modernity, with fossil fuels powering not only the expansion of capitalism but the political settlements, from imperialism to modern globalisation, built on it.

This historical understanding of climate change has led Malm to some specific conclusions: capitalism, not human beings, is changing the climate; industrialisation itself is less of a problem than the fossil system that powers it; the overwhelming focus of climate activism must be on dismantling fossil infrastructure; the chief problems with technology are the exploitative conditions of manufacture and the destructive ends to which it is put, rather than any more general concern about its destructive attitude to nature. Malm tends to focus on Europe and the US, as the architects and beneficiaries of fossil capitalism – and as polities that are both hugely influential and susceptible to popular pressure. His most recent book, White Skin, Black Fuel, written with the Zetkin Collective, a group of anti-fascist researchers based at the University of Lund, broadens this perspective, using particular historical or national examples to look at the entire fossil system from a new angle.

Consider the Amazon. During the Brazilian dictatorship of 1964 to 1985, the ‘green desert’ of the rainforest was opened up for speculators, gold-diggers and rubber-hunters, who brought chaos and destruction to the forest ecosystem, and everything from disease to torture to its indigenous peoples. The speed and scale of deforestation became a matter of international concern. By the 1990s, ‘cattle capitalism’ had led to more deforestation, with swathes of the Amazon felled for pasture. To follow the supply chains out from the ranches is to see much of the world become implicated in every razed square metre: the beef itself is served on tables in Russia or Italy, but the hide turns up in baseball gloves in the US and dog collars in Sweden, the tallow in shaving cream sold in Tokyo, the guts in the strings of tennis rackets, the hoof or horn in the keys of a piano, or rendered to thicken lipstick. The commodities that have their origin in the destroyed forest criss-cross the globe, each freight journey belching carbon into the atmosphere.

There is a perverse, monstrous sublimity to this vision. The Amazon, as a historic carbon sink, should feature prominently in any serious climate politics. Unlike the examples in Malm’s earlier work, however, the depletion of the Amazon is not directly connected to fossil fuel extraction (the most destructive mining in the Amazon is for minerals, especially iron). Cattle capitalists, like other pillagers of the green desert, are part of a vast sphere of secondary industries that are dependent on fossil capital, and share its rapacity and drive to expand. How far these industries can be divorced from their fossil predicate is one of the more awkward questions for mainstream climate politics; it’s hard to see how the destruction of rainforests, vast rare-earth mines or accelerating soil depletion could be justified even if powered purely by wind or sun.

Some politicians are unfazed by such issues. Jair Bolsonaro pledged during his campaign for the presidency that he would reverse the ‘industry of fines’ with which the Lula and Dilma governments had slowed the destruction of the Amazon. There was, he said, ‘still space for deforestation’: indigenous peoples could ‘adapt or vanish’, and he promised to proscribe the Landless Workers’ Movement. Anticipating his victory, the rate of deforestation spiked by 50 per cent. Five days after his triumph in the first round, Bolsonaro’s choice for foreign minister, Ernesto Araújo, declared climatism ‘a globalist tactic to scare people and gain more power’.

Over the past decade, Germany has been the world’s leading producer of brown coal. In 2019 it accounted for 21 per cent of emissions in the EU; in 2018 it was the world’s sixth biggest emitter of CO2 from fossil fuels. Germany’s lignite mines account for seven of the ten largest point sources of CO2 in Europe. Almost no single action would yield as significant a reduction in European emissions as the closure of these mines. But Lusatia, where many of the lignite pits are found, is also a stronghold of the far-right AfD: in 2017, the same year the Grosse Koalition contemplated closing these mines, the party won more than 30 per cent of the vote in the region. In the Bundestag, the AfD climate spokesman, Rainer Kraft, attacked what he called ‘eco-populist voodoo’; the party castigated Merkel for both a ‘disastrous asylum policy’ and a ‘left-green ideologised climate policy’. Under pressure from the AfD, the coal exit commission set an end date of 2038. This concession only emboldened the far right: in 2019, the top AfD candidates for Saxony and Brandenburg (neighbouring lignite states) met at their common border to declare their intention to mine coal for another thousand years – a duration not lit on accidentally by German nationalists.

[...]

These two stories form part of the dossier of evidence amassed in White Skin, Black Fuel. Subtitled ‘On the Danger of Fossil Fascism’, the book asks a deceptively simple question: why do so many parties and politicians of the far right traffic in climate denialism?† In Poland, Jarosław Kaczyński referred to alien Muslim-borne ‘parasites and protozoa’ while authorising the construction of new coal plants as a central platform of the Law and Justice party; his defence minister, Antoni Macierewicz, visited Europe’s biggest lignite facility to declare: ‘Poland stands on coal.’ In Hungary, Orbán’s Fidesz Party has promised undying loyalty to BMW and eternal vigilance against the Muslim migration supposedly sponsored by George Soros. In Finland, the Finns Party combines baseline anti-migration policies with warnings about the illness-inducing properties of wind turbines. In France, Marine Le Pen has claimed that ‘migrants are like wind turbines, everyone agrees to have them but no one wants them in their back yard.’ There are many more examples.

[...]

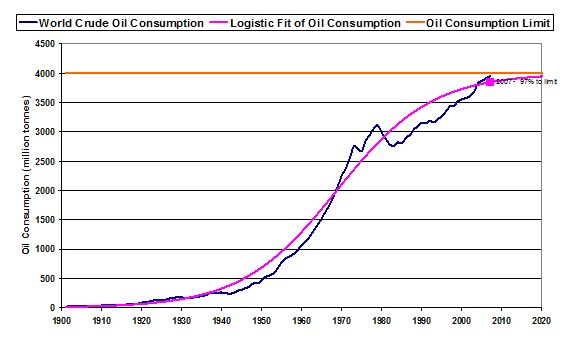

Justin Trudeau told a gathering of oil and gas executives that ‘no country would find 173 billion barrels of oil in the ground and just leave them there.’ Yet this is exactly what must happen. Few states have gone as far as Denmark and begun to end licensing rounds for hydrocarbon exploration. Trudeau’s line neatly articulates the logical position for any developed state enmeshed in global competition and trade. If it strikes us as irrational, it’s because the whole system is irrational.

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v43/n22 … y-wildfirethe LRB dedicated a few pieces in its last issue to timely writings on this topic, to coincide with cop26.

you never want to look beyond the economics or politics of your household/domestic budget. anything that involves a painful reckoning with the politics of your own citizens or nation involves feeble gestures towards 'brown people' or 'overpopulation', which sounds remarkably aligned with the far-right on this topic.

They see ‘fossil fascism’ as an emergent political formation, linking ‘primitive’ fossil capital – direct extractors, which can’t survive divestment – with racist politics. Aware of the slipperiness of definitions of fascism, they stick with the term because their new postulate has many of its hallmarks: fantasies of a nation purified of parasitical degenerates and outsiders; an indifference to mass death; emergence in an emergency where significant established economic powers are threatened.

sound familiar?

at the same time, you chide people for taking plane flights, as if the climate crisis can be averted by western consumers making better buying decisions – whilst their own states put their feet down on massive fossil-fuel expansion, often motivated by electoral politics and right-wing populism.

you are totally incoherent, in other words.

Last edited by uziq (2021-11-09 06:40:41)